这就构成了80年代的美术背景。事实上,到了文革后期,对文革绘画的霸权式宰制的不满就开始出现(冯国东很早就把人体画成绿色了),在80年代,这种不满越来越激烈,很快,一批年轻的艺术家就执意冲破它的桎梏,在绘画语言和观念上出现了面向西方传统——一个丰富的、多样性、充满杂质的西方传统——的爆炸性转折。

王音的艺术学徒期刚好在这个时期(80年代中后期)结束。此时,西方的现代主义和文革模式,这两种绘画经验,正在进行紧张的矛盾对峙。同那个时期的大部分人一样,他少年时期的绘画经验,毫无疑问是在苏派绘画传统中生长出来的,他对这个传统烂熟于心——不仅是苏派绘画传统,而且还包括俄罗斯和苏联的文学和思想传统。同样,他的大学时光,正好是被西方人文思潮和美术思潮所“震撼”的时光。这也使他对当时的来自西方的先锋派思潮,尤其是美术和戏剧方面的先锋思潮非常了解——他甚至对国内现在还不甚了然的安东尼•阿尔托有过专门的研究。当时,在北京,新的艺术潮流就是用西方的先锋派经验来取代苏式绘画经验和文革绘画经验,并借此对美院传统和强大的官方绘画意识形态进行挑战。西方“新的”现代主义和后现代主义艺术潮流,在北京的文化领域开始流行,像鸦片一样吸引着形形色色的文艺青年,以至于80年代“进步的”美术界狂热地从西方那里吸取营养。就是在这样一个氛围下,王音开始了他的艺术生涯,但是,多少有些奇怪地,他并没有被他所熟悉的这种新艺术潮流完全吞噬,相反,他细致地研究了它们,并吸收了其中的精髓,但他却执意地同它们保持着距离。当然,这也决不意味着他被苏式绘画和文革绘画经验所降伏。王音的方式是,要寻找一种有活力的绘画可能性,要在绘画中重新点燃自己的激情,就务必要寻找另类路径,只不过这条路径并非当时大多数人选择的“新的”西方路径。相反,王音不合时宜地从“老的”路径中去寻找。而王音自己寻找的这种另类路径,构成了他基本的艺术观念和方法论。

这是怎样的一条路径?事实上,我们从王音早期的“小说月报”系列就可以发现,王音的目光不是盯住西方,而是盯住五四以来的中国文人传统。受当时知识分子对新文化运动讨论的影响,王音重新研究了一批早期中国画家,如徐悲鸿、颜文梁、王式廓等人的绘画。他将这些画家及其作品置放在整个中国现代思想的背景之下来考虑,并将他们作为中国文化现代性进程中的一个重要部分来对待。因此,对这些作为中国现代油画的“起源”的代表性人物的谱系学探讨,在某种意义上,就是对中国文化现代性谱系的探讨的一部分,王音对文化现代性进程充满着兴趣。就绘画现代性而言,他从现在出发,一步步地逆向地推论其“起源”何在?就个人而言,这样的谱系学问题或许是:我的绘画经验来自何处?我为什么形成了自身的风格?我为什么这样绘画?就整体而言,当代中国绘画(油画)经验来自何处?当代中国绘画(油画)为什么会出现这样的形态?中国的绘画现代性是怎样植根于整个中国文化现代性的内在进程之中的?这是典型的福柯式的谱系学工作。显然,这项谱系学式的工作,就同整个80年代的艺术状态迥然不同。在80年代,绘画基本上不去有意识地回溯性地自我反思,而只是充满本能地厌恶文革经验,并且充满本能地进行意识形态的表达。在那个时期(甚至是现在),绘画通常是执著地对现时代表态,是艺术家情绪、主体和意志的瞬间性流露,绘画总是铺满着强烈的批判性的个人激情和态度。但是,我们看到,王音的绘画非常冷静,非常理性,甚至是——如果我们仔细地看的话——对现时代视而不见。他的目光总是专注于绘画史上的过去,而不是社会生活史中的现时。这种对现时不介入的绘画,同样充满着批判,只不过是,这种批判不是意识形态的批判,而是对绘画本身和绘画历史的批判。专注绘画史上的过去,在某种意义上,并不是对现时进行回避,而是探讨现时的另一种方式:研究过去,并不是要沉迷于过去,并不是要在过去中玩味和流连忘返,相反,研究过去,就是要力图解释现在:现在是怎样从这个过去一步一步地蹒跚而来?

在这个意义上,王音不是用绘画来对外在的世界进行表态,而是用绘画来研究绘画,是借绘画来对绘画自身进行反思、置疑和批判,更为恰当地说,是通过对绘画史的表态来对现时代表态,是通过绘画来对绘画现代性进程的表态,最终是通过绘画来对文化现代性进程进行谱系学式的考究性表态。

那么,王音是怎样具体地来进行这种谱系学考究的呢?王音对现代中国的油画经验进行了饶有兴致的分析。事实上,中国的现代油画经验一直被一种焦虑感所折磨: 这种缘自于西方的绘画语言,到底怎样在中国才能找到它最为合适的表述方式?能否找到这样一种合适的方式?油画如何植根于中国语境?艺术家如何能够借助这种西方语言进行自我叙事和自我表达?被移植的中国油画经验较 之西方而言有什么独特之处?如同中国的文化现代性始终无法脱离中西文化的对峙状态一样,中国的油画现代性经验同样处在这一中西文化对峙状态之下。大量的艺术家都对此做过摸索式的试验,都在探讨一种恰如其分的油画语言形式和表达形式。我们看到,一种融合和沟通中西两种绘画语言的努力和意图,在二十世纪顽强而执著地浮现,这种融合的目的,就是为了缓解西方语言和中国语境之间的不适所造成的焦虑感,就是为了创造出一种新的绘画语言。而王音的作品,并不是沿着这个路径去寻找或者创造一种新的油画语言形式,王音并不打算为油画的现代性开辟新路,相反,他是对这种开辟新路的方式,对这种创造油画语言形式的努力,对现代中国油画的书写历程,对绘画现代性进程中的重要“事件”,以及包裹这些事件的历史语境,进行回溯性的反思——这种反思与其说被一种强烈的使命意识所充斥,不如说被一种游戏式的欢快态度所浸染。正是这样创造新油画语言的努力和意图,这样追寻中国油画现代性的欲望,构成了王音作品的批判性主题。

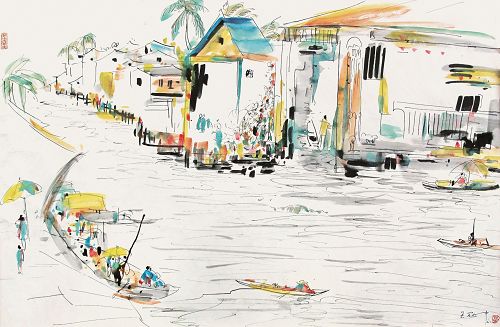

这样,我们看到,王音的作品不断地出现早期中国油画的经典要素,并且总是闪现出某些油画经典中的“痕迹”,这些“痕迹”正是中国绘画现代性历程中的决定性要素。王音不断地对它们意有所指地回溯,戏仿,模拟和指涉,也可以说是不断地为这种痕迹重新刻上痕迹。在这个意义上,王音的作品就是试图为20世纪的绘画现代性经验铭刻痕迹。这些痕迹多种多样,有可能是一件代表性画家的作品(比如徐悲鸿的一张画),有可能是绘画史上的一个经典题材(比如文革时期的芒果),有可能是一种霸权性的绘画技术(六七十年代主宰性的苏式绘画),有可能是一种特定历史条件催发出来的绘画观念(延安画家对民间绘画技术和题材的挪用),有可能是绘画中的充满权力关系的主体对他者的凝视(一些开拓性和试验性的画家将西藏等少数民族风情作为绘画题材),也有可能是典范性的绘画教育机器和体制(美术教育中对石膏像的写生),等等,所有这些,都是中国绘画现代性经验中的重要痕迹。它们构成了绘画“事件”,这些“事件”编织了二十世纪中国油画现代性的谱系,它们曾经是激进的乃至主宰性的,只不过现在被今天新的绘画事件所压抑而变得沉默无声。王音借助于他的绘画,将这些一度被湮没的痕迹重新擦洗干净,让这些消失的历史重新发出自身的历史光芒,并在今天让其命运遭到历史的审视。这,就是王音工作的主要意图之所在。

但是,如何复现这些绘画痕迹和“事件”?王音的复现方式流露出了某种达达主义式的气质:简洁、富于穿透力、一针见血,最重要的是,这种方式并不沉重,相反还充满着喜剧性的游戏态度。他的工作风格呈现出“差异的重复”,也即是说,他重复那些绘画事件,但是这种重复是带有差异的重复,是不完全的重复,是添加、减少或者细节改动性的重复,是在原有绘画事件中添加了异质要素的重复。正是在这个意义上,我们说,那些经典性的绘画痕迹和事件是在他的作品中“闪现”。王音重现这些绘画事件和痕迹的方式多种多样,他有时候直接在画布上进行喷绘;有时候挪用民间画师的作品并进行重写,有时候直接运用苏式绘画技术来戏拟这种技术;有时候通过凝视他者的方式来指涉一个凝视他者的作品;有时候用不同的绘画材料来复现一个原初的画面;有时候修改原作的局部(添加、减少或者改变一点)来“延续”原作。王音的这些方式,将那些绘画事件和痕迹重新从记忆的抽屉中翻掘出来,并迫使人们面对20世纪中国的绘画现代性历程。

那么,今天的绘画该如何面对这个现代性历程?我们能否在这个历程中重新发现自己的绘画语言?能否在这个地域意识和文化意识越来越淡薄的时代找到自己独特的表达方式?这是王音针对中国绘画现代性历程提出来的问题,但是,这些严肃的问题——正如历史一再显露出来的那样——并没有答案。王音的作品,并非要回答和解决这些问题。当然,他也不是要发明一种新的绘画语言,或者,更恰当的说法是,在他这里,存在着一种绘画语言,只不过,这种绘画语言,是对既有绘画语言的嬉戏;同样,他也不愿意对二十世纪中国绘画现代性的历程做出评述,他不愿意判断,他只是指涉、暴露和显现,只是在这些指涉和暴露中对这个绘画现代性进程进行体验和感受,他只是通过绘画的方式,以体验和感受为乐。艺术,借此返回到了它的基本欢乐:艺术在自我指涉的游戏中所感受到的欢乐。

How to "Recapture" the Experience of Painting?

By Wang Min”an

In short, the tradition of Chinese oil painting in the 20th century consisted of two divisions. One was the tradition of Western painting (this tradition included the Western realist tradition since the Renaissance and the modernist tradition after the 19th century. The other was the Soviet tradition following the 50s, which was the socialist modernist tradition. In the early 20th century, the tradition of Western painting dominated the practice of Chinese oil painting. During this period, students who had studied abroad returned home from Japan and Europe, and distributed all kinds of experiences related to Western oil painting around China, while dialogues and clashes among realism and various modernist movements unfolded. The heterogeneous nature of oil painting in style was stimulated and circulated. However, behind this vivid and sophisticated experience about oil painting, the cultural anxiety typical of that age was also spread in the circle of painters: would this painting style and model derived from the West fit in with the Chinese context? Could it make "negotiation" with Chinese painting? Would it lead to the launch of what Homi K. Bhabha referred to as "the third space"? Wang Yuezhi, Lin Fengmian, Xu Beihong and the others were tortured by the anxiety about this language. They strived to "invent" a new "modern" painting language from two traditions. They all tried to open up the "third space" for painting. We can regard this experiment with the language of painting as the initial modernist approach in Chinese painting. The will power to invent new painting languages was suppressed by historical conditions in the 40s. Meanwhile, like literature, there was a tendency in painting to free itself from being intensely stylized, in order to generate pure political "intervention" with history. In this background, there emerged a powerful "Yan”an fine arts model". The masses and civilians were both the target audience that this Yan”an model "called for" as well as the subject for this model. Painting began to linger in the view of the people. In the 50s, this Yan”an genre carried out positional-warfare style and extremely turbulent "negations" with the Russian socialist modernist system, and subsequently invented a painting tradition of the Cultural Revolution by the time it reached its maturity. This highly stylized and politicized realist painting constituted another substantially developed and systemized modernist painting category of the 20th century in China. In the latter 20th century, it expelled the Western modernist tradition at one blow, while constrained the early modernist painting experiments of Lin Fengmian and the others to unite Chinese and Western traditions.

This was the context for fine arts in the 1980s. In fact, in the later period of the Cultural Revolution, dissatisfaction with the hegemonic dominance of the Cultural Revolutionary painting began to emerge (Feng Guodong had painted a human body in green very early on). In the 80s, this frustration was getting more and more radical. Soon, a group of young artists were determined to break free of its shackle. Concerning the language and concept for painting, there was an explosive transition towards the Western tradition, a rich and diverse Western tradition that was full of impurity.

Wang Yin”s training as an art apprentice happened to end during this period (the middle and later periods of the 80s). At this point, two painting experiences, the Western modernist genre and the Cultural Revolutionary system, were in the heat of intense opposition. Similar to the practice of most people of the same period, his painting experience from his boyhood undoubtedly grew out of the Soviet painting tradition. He knows this tradition by heart - not only the Soviet painting tradition, but also Russian and Soviet literature and tradition of thinking. Meanwhile, his time in university was just the period that was "shaken" by Western humanistic trends of thoughts and fine arts theories. This allowed him to be fully exposed to the avant-garde trends of thoughts from the West, especially those in fine arts and theatre - he even specifically studied Antonin Artaud, a largely unknown figure in China even today. At that time in Beijing, the new trend in art was to replace the Soviet and Cultural Revolutionary painting experiences with Western avant-garde experience and in this way challenge the tradition of art academies and the powerful official ideologies of painting. Western "new" modernist and post-modernist trends in art began to be widespread in the cultural arena in Beijing and attract all kinds of young people interested in literature and art like opium. As a result, the "enlightened" art circle of the 80s fanatically absorbed their nutrition from the West. It was in such an atmosphere that Wang Yin embarked on his art career. However, somewhat strangely, he was not completely swallowed by the new art trends that he was familiar with. On the contrary, he studied them meticulously, drew on the best part of them, while persistently keeping a distance from them. Of course by no means did this mean that he was tamed by the Soviet and Cultural Revolutionary painting experiences. Wang Yin”s approach was to look for a vital possibility for painting. For him to rekindle his own passion in painting, he must look for an alternative path. But it was not the "new" Western path that most people pursued. Contrarily, Wang Yin dug into the "old" way for his search. This alternative path that Wang Yin took on his own constituted the fundamental concept and methodology of his art practice.

What kind of path was it? Actually, we can discover from Wang Yin”s early "Fiction Monthly" series that his gaze is not on the West, but on the Chinese scholarly tradition ever since the May 4th Movement. Influenced by the discussion of the new cultural movement by the intellectuals of that time, Wang Yin restudied the works of a group of early Chinese painters such as those of Xu Beihong, Yan Wenliang, and Wang Shikuo etc. He examined these painters and their works in the context of the entire Chinese modernist view and considered them as an important part of the modernistic process of Chinese culture. Thus the genealogical study of these representative figures of the "origin" of Chinese modern oil painting, was, to a certain extent, part of the discussion of the genealogy of the modernity of Chinese culture. Wang Yin was fascinated with the modernistic evolution of culture. Regarding the modernity of painting, he departed from the present, conversely traced down to its "origin" step by step. From an individual”s point of view, the genealogical issues involved would probably be: Where has my painting experience come from? How have I developed my own style? Why do I paint in this way? From a general point of view, where has the experience of Chinese painting (oil painting) come from? Why has such a style existed in contemporary Chinese painting (oil painting)? How is the modernity of Chinese painting embedded in the internal modernistic evolution of the whole Chinese culture? This is a typical Foucault style genealogical way of working. Obviously this genealogical project was widely different from the state of art during the entire 80s. In the 80s, there was basically no conscious and retrospective self-reflection on painting. There was simply plenty of instinctive disgust by the Cultural Revolutionary experience as well as instinctive expressions of ideology. At that period (even till now), more often than not, painting was indefatigably the declaration of the present times, the momentary revelation of the artist”s emotions, concepts and will. Painting was always charged with intense and critical personal passion and viewpoints. However, as we can see, Wang Yin”s paintings are extremely calm and rational, and even, if we look closely enough, turn a blind eye to the present. His attention is always focused on the past of the painting history, instead of the present of the social life history. These paintings that refuse to intervene with the present, are equally filled with criticism, except that this criticism is not a critique of ideology, but an analysis of painting itself and the history of painting. His fascination with the past of the painting history, in a certain sense, doesn”t mean that he intends to avoid the present. It”s simply another approach to discuss the present. To study the past isn”t about being obsessed with the past, or relishing and being trapped in the past. Contrarily, to look into the past is an attempt to explain the present: how has this present stumbled forward one step at a time from this past?

In this sense, Wang Yin doesn”t observe the external world with painting. Instead, he studies painting with painting. He makes use of painting to contemplate, question and critique painting itself. To be more accurate, he comments on the present by discussing the history of painting and accounts for the modernistic progression of painting through painting, and eventually provides genealogical and investigative observations on the modernistic development of culture through painting.

How has Wang Yin actually executed such genealogical research? Wang Yin made rewarding analysis of the system of modern Chinese oil painting. Actually, the experience of Chinese modern oil painting has been troubled by a sense of anxiety: how on earth can this painting language that has stemmed from the West find the most appropriate way of expression in China? Can it find such a perfect expression? How is oil painting imbedded in the Chinese context? How can artists rely on this Western language to generate self-narration and self-expression? What is unique about the transplanted experience of Chinese oil painting in comparison to its Western counterpart? Just as the modernity of Chinese culture is never released from the confrontational state between Chinese and Western cultures, the modernity of Chinese oil painting is equally stuck in the same opposition between Chinese and Western cultures. A large number of artists have made tentative experiments in this aspect. They have all been pursuing an appropriate style and way of expression for oil painting. We can see that an attempt and intention to merge and bridge the two painting languages of China and the West doggedly and persistently rose in the 20th century. The purpose of such fusion is to reduce the sense of anxiety resulting from the discomfort between a Western language and the Chinese context, in order to invent a new painting language. However, Wang Yin”s practice hasn”t followed this path to pursue or create a new language of oil painting. Wang Yin doesn”t desire to open up new possibilities for the modernity of oil painting. On the contrary, he reflects backward on the way to explore new paths, the attempt to invent languages of oil painting, the written history of modern Chinese oil painting, the key "events" in the modernistic process of painting, as well as the historical context that contained these events. This reflection is infatuated by a playful joy rather than being dominated by a strong sense of responsibility. Such an attempt and objective to conceive a new language for oil painting and such a desire to trace back to the modernity of Chinese oil painting constitute the critical subject of Wang Yin”s works.

In Wang Yin”s works, there are the recurring appearances of classic elements in early Chinese oil paintings and flashes of "marks" from certain classic oil paintings. These "marks" were the shaping elements in the modernistic evolution of Chinese oil paintings. Wang Yin tirelessly looks back upon, mimics, copies and involves them or in another word, diligently inscribes new marks upon these marks. In this sense, in Wang Yin”s works, he tries to stamp imprints upon the modernistic experience of painting in the 20th century. These imprints are of a great variety. It”s likely to be a work of a representative painter (for example, a Xu Beihong”s painting), or a classic subject matter in the history of painting (for example, a mango of the Cultural Revolution), or a leading painting technique (the Soviet style of painting that governed the 60s and 70s), or a painting concept catalyzed by a certain specific historical condition (Yan”an painters” appropriation of techniques and subjects from folk paintings), or the gaze of the powerful principal body at the others in painting (some adventurous and experimental painters adopted the life and culture of ethnic groups from Tibet as their subject matters), or the educational machine and system based on exemplary painting (painting from plaster statues in fine arts education) etc. All of these are important imprints in the modernistic experience of Chinese painting. These are the painting "occurrences"; these "occurrences" are woven into the genealogy about the modernity of Chinese oil painting in the 20th century. They were once radical and even dictating and are simply reduced to silence today by new painting experiences. Through his paintings, Wang Yin polishes and renews these imprints that were once annihilated, allowing the fading history to restore its own historical glow and allowing its fate to be examined by history today. This, is the real purpose of Wang Yin”s practice. Then again, how to reintroduce these marks and "occurrences" of painting? Wang Yin”s way of reiteration reveals a certain Dadaist quality: concise, highly penetrable, and straight to the point. What is more important is that this approach is not heavy. It”s however full of comical and playful outlooks. His style of working shows the "repetition of discrepancy," that is to say, he repeats those painting events but his replication is done with alteration, rather than just absolute reproduction. It”s repetition with addition, reduction or change of details. It”s repetition that adds heterogeneous elements into the original painting events. It”s in this sense that those classic imprints of paintings and incidents "flash" in his works. Wang Yin has a multitude of ways to recapture these painting occasions and imprints. Sometimes, he directly sprays onto images; sometimes, he appropriates works by folk art painters and rewrites them; sometimes he directly borrows the technique from Soviet paintings to playfully imitate the very same technique; sometimes he involves a work that gazes at the others by gazing at the others; sometimes he restores an original painting with different painting materials; sometimes he alters parts of the original (by adding, reducing or changing slightly) to "extend" the original. Through these methods, Wang Yin unearths those painting experiences and imprints from the drawer of memory and forces people to confront with the modernistic progression of Chinese painting in the 20th century.

So how does painting deal with modernity today? Can we re-discover our own painting language during this modernity? Can we uncover our unique means of expression at a time when the awareness of regional and cultural characters is getting less and less? These are the questions that Wang Yin has put forward in relation to the modernity of Chinese painting. However, these serious issues - as it”s revealed by history again and again - do not have answers. Wang Yin”s works are not meant to answer or solve these issues. Naturally, he doesn”t want to invent a new painting language either. To be more precise, there lies a painting language here with him. It”s just that this painting language is a play on the existing painting language. Meanwhile, he”s not wiling to provide any statement on the modernistic evolution of Chinese painting in the 20th century. He”s not willing to make judgment. He only makes references to, exposes and illustrates, simply experiences and feels the modernity of painting. He simply takes delight in experiencing and feeling through painting. Art thus returns to its basic joy: the pleasure experienced by art in the game of self-reference.

- 推荐关键字:“重现”绘画经验

- 收藏此页 | 大 中 小 | 打印 | 关闭

- ·如何“重现”绘画经验?

- 2007-08-29